|

Stardate

20030120.1459 (Captain's log): Fighting a war isn't like baking a cake, where you look up a recipe and follow it, and end up with something nice and fluffy and flavorful, and each time you want to make a cake you follow the same recipe.

Every war is unique. Situation change. What led to a huge success last time might fail miserably this time. You always have to take the situation into account, and in particular as the weapons we use change the way we fight wars also has to change. Because if you don't, the only thing you're going to have to show for your efforts is vast numbers of dead bodies and a ruined nation.

That is generally accepted as the lesson of the first years of the western front in WWI. A style of warfare which began before Gustavus Adolphus, which was developed by Frederick the Great, perfected by Napoleon, had finally became a form of mass suicide in face of the triple threat of barbed wire, machine guns and effective massed long range artillery. Mass charges by large formations of men had already become extremely perilous by the time of the American Civil War, where they sometimes were effective but sometimes spectacular failures. There were further failures in Crimea and in the Franco-Prussian war, but there were enough successes in all three that it was not realized that it was rapidly becoming obsolete.

Pickett's Charge failed because massed musketry had become too good. Fire rate was high, range was long and the bullets were highly lethal, and the attackers had to pay too high a price simply to cover ground to reach the defenders. When the defenders were also up a hill, in good morale, behind a fence, and supported by artillery there was virtually no chance, and the men of Pickett's division got slaughtered.

The "modern way of war" was developed more or less in the 1930's and was first used effectively by Germany. It was then adopted by those Germany faced, who were able to do it better mostly because they had more men and more equipment. Probably the canonical example of it was the Normandy invasion. You bring immense amounts of men and matériel into the theater, ready to be used when the time comes, use intense air preparation to weaken the enemy, hit him and then never let up. And everything depends on concentrating the forces needed before you begin.

But modern air power presents you with a dilemma, if the other side has it and can use it against your ground forces. That's what the Germans faced when they prepared their last offensive of the war, known to most of us as the "Battle of the Bulge". An entire force was prepared in the West, unsuspected by the western Allies, and thrown at a weak section of the American part of the front. The attack was timed for a period of bad weather because it meant that the Allied air forces couldn't fly. And it's a matter of record that one reason for the failure of that assault was that the weather cleared. Allied planes (especially American fighter-bombers) were able to fly again, and not only could they learn where the Germans were, but could also begin to bomb them and disrupt movement of supplies.

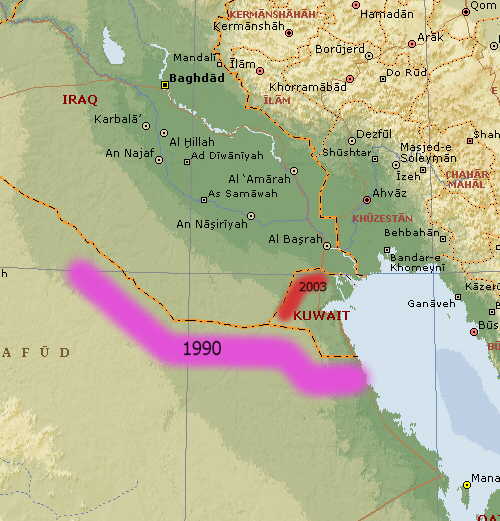

In 1990 and 1991, in the first Gulf war, we methodically prepared a large force inside Saudi Arabia, moving men and equipment in over a period of months. Once the force was ready, six weeks of air preparation began. During that time the air was cleared of Iraqi planes, and while it continued Schwarzkopf ordered his grand left-movement of a large part of his force to be in position for the "left hook". Then, once that was ready and when it was judged that the Iraqi combat power had been sufficiently eroded, ground ops began.

We can't do that now. We can't fully build up before beginning ground operations. The situation has changed in several critical ways.

It appears now that the ultimate force we'll use will be smaller than in 1991. Then the combined force of Americans and others was in the range of about half a million; this time it looks as if it will ultimately be about half that, maybe a bit less. But in 1990 and 1991 we were deploying in Saudi Arabia and had an immense area to work with. This time it looks like most of the deployment will be in and through Kuwait. Much of that can't be used either because it's populated, or because it's their oil fields, or because it's full of left-over mines and unexploded ordnance from the last war. So the total area available for initial deployment is much smaller, and if we moved the entire force in before combat began, they'd be highly concentrated and would become a fat target for some sort of area attack by WMDs.

The force this time will be smaller but the area we have to work with is much smaller, and concentration would be much higher.

We know that Iraq has large amounts of chemical weapons (including mustard and nerve gases), and while our forces are equipped and trained to fight through such things, doing so is highly treacherous because it is extremely unforgiving. Even a small mistake can lead to death. A large initial concentration of our men in Kuwait would be an inviting target for something like a short-range attack by chemical-tipped rockets, or even a long range attack by several simultaneous Scuds.

We also can't ignore the possibility that Iraq actually has managed to create a nuke, and if that's true and if they can fit one into a Scud, then it becomes a really serious threat.

This kind of thing is dealt with as a series of layered defenses. For short range ro

|